From Normans to Nando’s

What is an indigenous Brit anyway?

Benjamin Zephaniah once wrote a genial little recipe-poem called The British (Serves 60 Million). It begins deep in the mists of antiquity — Picts, Celts, Romans, Normans — and then, with the delicacy of a microwave ping in a fine restaurant, leaps straight to “add some Jamaicans, Dominicans, and Sudanese.” As though England spent the intervening millennium politely waiting for the next ingredients to arrive.

It’s hard to think of a more jarring chronological pratfall. A thousand years of history skipped like a scratched dub-plate. The English go to bed medieval and wake up multicultural, blinking at the kettle.

To be fair, Zephaniah wasn’t writing a sociology textbook. His poem is a celebration of modern Britain as a recipe: cheerful, inclusive, and a bit spicy. But the jump is revealing. We have become oddly shy of our own continuity. To be English is to exist between two embarrassments: a past that is too imperial to boast about, and a present too fragile to believe in. So we skip the awkward middle, stir in some global ingredients, and tell ourselves we’ve always been a melting pot. It’s comforting, but untrue. We did not appear fully cooked in 1950, we slow-roasted over hundreds of years.

But, the poem raises a curious question: if everyone in Britain today is a blend, does anyone get to be indigenous? The term itself has become radioactive. To describe oneself as “indigenous English” sounds, depending on the audience, either reactionary or ridiculous. Yet surely we are of this land in some real sense. Our ethnogenesis — the moment when “we” became recognisably English — happened here on this soggy archipelago, amid the fog and hedgerows, before empire, before tea, and even before Marmite-flavoured Monster Munch.

So, to avoid further outrage, let’s approach the issue methodically by devising a diagnostic tool; a sort of pub-friendly anthropology test. After all, if you can’t quantify your existential confusion in numbered stages, are you even British?

The Five Types of Indigenousness

A guide for the confused.

Type 1: The Palaeo-Realist

You were literally here first. You have blood-memory of ice floes and mammoths.

By this measure, no one in modern Britain really qualifies; our Mesolithic cousins packed up long ago, leaving behind arrowheads and and very little in the way of continuity. The English get a “nice try” sticker and a complimentary fossil from Lyme Regis.

Score: 0 / 5.

Type 2: The Ethnogenesis Enthusiast

Your people became “a people” here.

This one we pass. The English identity wasn’t imported like a flat-pack from Saxony; it was assembled clumsily on site. Our ancestors — those Germanic settlers, Norse raiders, and Norman HR managers — merged into something distinct on this island. The language, the habits, the fatalism, all of it fermented locally.

Score: 5 / 5.

Type 3: The Legal Anthropologist

You descend from a pre-colonial population, now marginalised by a dominant one.

Here the English flunk magnificently…at least for now. We were always the dominant one. Nothing kills your claim to indigeneity like inventing the East India Company. Applying the UN definition to the English is like letting the referee call themselves the underdog.

Score: 0 / 5.

Type 4: The Romantic Ecologist

Indigenousness as emotional bond: a deep, mossy, Wordsworthian intimacy with the land.

Here, the English shine again. We’ve written more love poetry to mud than any people alive. Hardy’s Dorset, Tolkien’s Shire, Housman’s blue forgotten hills, and even the BBC shipping forecast — all hymns to the temperate melancholy of home.

The problem is the industrial hangover. It’s hard to claim sacred kinship with the soil when you covered much of it with Tarmac and Barratt Homes. And so our national spirit oscillates between pastoral reverence and planning permission.

Score: 4 / 5

Type 5: The Postmodern Ironist

Everybody came from somewhere else; identity is performance; indigenousness is a marketing term.

Here we simultaneously pass and fail. We are both coloniser and colonised, ancient and amnesiac, proud and mortified. The language of Shakespeare conquered half the planet but came home speaking MLE.

Score 3 / 5.

By my calculation we score a gentlemanly 12 out of 25. Not bad. Indigenous enough to say we truly belong, but we don’t want to make a scene. We sometimes seem to be both the host and an intruder at our own dinner party.

What the Zephaniah skip really exposes is our refusal to narrate ourselves. Between the Norman invasion and the Windrush arrivals, we have a millennium of cultural continuity that we treat as either boring or shameful.

But identity is a story we must keep telling or it falls apart. When we deny our roots, we don’t become cosmopolitan; we become forgetful. A people unsure whether it has the right to exist cannot create anything lasting, least of all the stories about themselves.

This is never more apparent than on our national day, when armies of commentators take to social media to remind everyone of the lack of indigenousness of our national patron. “Saint George was Turkish!”, they cry. “He came from Palesteine, he was a migrant” they chant in chorus. And although it’s tempting to counter by insisting St George was an Englishman who played cricket, enjoyed a full English Breakfast and a pint of mild, sadly non of these things are true. What we need is a better story.

Instead, all we have is a sense that Britain is a once-great garden now left to seed. “Managed decline” is our new national myth. We perform our decay with a kind of weary dignity, as if the Blitz spirit now applies to the slow-motion collapse of the high street.

But decline isn’t destiny. It’s a habit, and habits can be broken. The English once built cathedrals that took centuries and railways that crossed continents, but now we can’t build a bypass without a lengthy public inquiry. Somewhere along the way we traded ambition and stewardship for excessive self-consciousness.

So let’s drop the nostalgia, and have some nerve, and the kind of pride that’s based in hope and responsibility rather than tribes and genes (we can leave that to others). To call ourselves indigenous should not be a matter of purity and exclusion, but of care — for this island, its language, its weather, its withered towns, and its people, with their peculiar genius for muddling through.

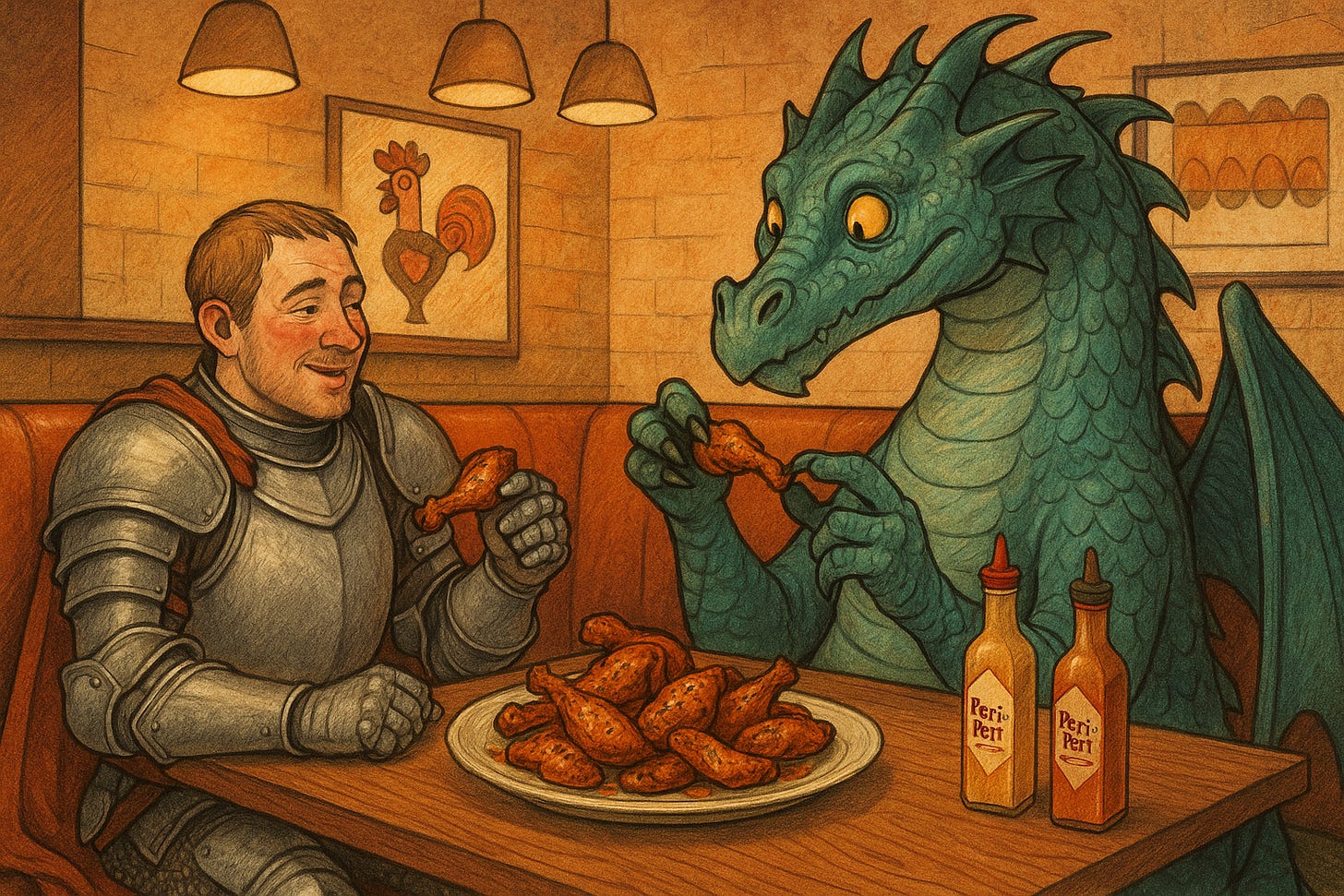

As for St George, perhaps he really was a Palestinian cricketer who liked hummus and marmalade. But wherever he came from, he can uniquely represent us. For we are a people who, when presented with a problem, are just too polite to fuss—until the problem becomes the size of a fire-breathing dragon which drags off the town’s fair maidens. And at that point…well, let’s see.